Portraits of a divided neighbourhood

Hebron is the only place in the West Bank where Jewish settlers and Palestinians live and work side by side. Edward Platt reports on a unique art project aiming to forge links between the two communities.

Nawal Slelmiah – the only female stallholder in the market in the Old City of Hebron, or El Khalil, as it’s called in Arabic – attaches great significance to the black and white portrait on display among the hand-woven clothes and fabrics in her shop. Before the British artist, Caspar Hall, arrived in Hebron for a three-month residency sponsored by Art School Palestine, no one had ever painted her portrait before. More importantly, she believes the portrait sends an important signal to the Israeli settlers and soldiers who often pass her shop near the entrance to the souk. “They often stop and look at it, and it tells them that it’s my shop – I’m the owner, and I’m not leaving,” she says.

Ownership is a vexed issue in Hebron, for it’s the only place in the West

Bank where settlers and Palestinians live side by side. For hundreds of years, a small community of Jews lived in Hebron until many were killed in a riot in 1929. After the Six Day War of 1967, in which the state of Israel expanded its borders by occupying the West Bank, Gaza and the Golan Heights, a small group of settlers returned to re-establish a Jewish presence in Hebron. At first, they were housed in an army camp and a settlement on the outskirts of the city, but in 1981, they returned to the city centre, and occupied a building that had once been a Jewish clinic. Their number has now grown to 850, and they are guarded by a large contingent of Israeli soldiers.

In 1997, under the Oslo Accords, Israel relinquished 80 per cent of Hebron to the Palestinian Authority, but it retained control of the area around the Old City, where the settlers live. The arrangement has not brought peace to Hebron – there are frequent clashes between the settlers and their Palestinian neighbours, and many Palestinians left the Old City.

In the last few years, efforts have been made to reverse the decline. The

Hebron Rehabilitation Committee has renovated dozens of shops and houses in the Old City, and it subsidises rents to encourage Palestinian families to return. The population has risen again to around 5,000, though there are still hundreds of empty shops and houses, and the once thriving market has fallen into decline.

Rabe’ Zeahdi – another of the market traders who sat for Caspar Hall – inherited his stall from his father, who had owned it since 1948. In the past, he said stallholders could earn enough to feed a family of 10. Now, most of them have to beg to earn a living. This is a view clearly reflected in the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs’ report (published in July 2007), which revealed that an estimated 75 per cent of Palestinians live below the poverty line.

For the three-month art project, Hall moved to the Old City in February 2008 and set about befriending the stallholders. He learned Arabic, and eventually was welcomed as one of the family. In the end, the project proved so popular that he had to turn away many would-be sitters.

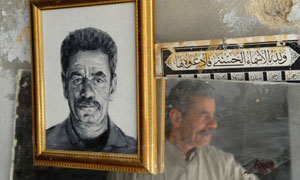

The simple black and white tones of his pictures, and their matching gold frames, imposes a unity on the sometimes fractious and squabbling stallholders, and at the same time, the meticulous portraiture rejects dated portrayals of Fedayeen fighters or what Halls calls “traumatic realism” – images of bereaved Arab women, and destruction wrought by IDF tanks or bulldozers. In all, he painted more than 70 portraits, compiling a unique social document of the market at a crucial stage in its history.

When he left, he gave the stallholders their portraits and told them that they could do what they liked with them. The response was surprisingly consistent: one or two are rumoured to have sold them, one gave his to his oldest son who is serving a life sentence in an Israeli jail, but most of them put them on display in their shops.

An exhibition of Hall’s work, which took its title from an old Arabic saying – 40 Days in Hebron and You Are a Khalili – officially opened last Sunday with a tour of the Old City to inspect the paintings, and for once, the stalls were open into the evening. Emad A Hamdan, the publicity director of HRC, said it created the kind of bustle and movement that the market needs, and he believes that the stallholders relished the experience: “It’s a sign of moral support,” he said. “I saw in their eyes how much it means to them.”